Extends

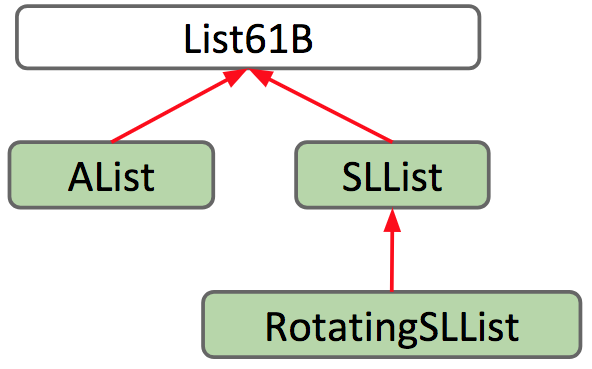

Now you've seen how we can use the implements keyword to define a hierarchical relationship with interfaces. What if we wanted to define a hierarchical relationship between classes?

Suppose we want to build a RotatingSLList that has the same functionality as the SLList like addFirst, size, etc., but with an additional rotateRight operation to bring the last item to the front of the list.

One way you could do this would be to copy and paste all the methods from SLList and write rotateRight on top of it all - but then we wouldn't be taking advantage of the power of inheritance! Remember that inheritance allows subclasses to reuse code from an already defined class. So let's define our RotatingSLList class to inherit from SLList.

We can set up this inheritance relationship in the class header, using the extends keyword like so:

public class RotatingSLList<Item> extends SLList<Item>

In the same way that AList shares an "is-a" relationship with List61B, RotatingSLList shares an "is-a" relationship SLList. The extends keyword lets us keep the original functionality of SLList, while enabling us to make modifications and add additional functionality.

Now that we've defined our RotatingSLList to extend from SLList, let's give it its unique ability to rotate.

Exercise 4.2.1.

Define the rotateRight method, which takes in an existing list, and rotates every element one spot to the right, moving the last item to the front of the list.

For example, calling rotateRight on [5, 9, 15, 22] should return [22, 5, 9, 15].

Tip: are there any inherited methods that might be helpful in doing this?

Here's what we came up with.

public void rotateRight() {

Item x = removeLast();

addFirst(x);

}

You might have noticed that we were able to use methods defined outside of RotatingSLList, because we used the extends keyword to inherit them from SLList. That gives rise to the question: What exactly do we inherit?

By using the extends keyword, subclasses inherit all members of the parent class. "Members" includes:

- All instance and static variables

- All methods

- All nested classes

Note that constructors are not inherited, and private members cannot be directly accessed by subclasses.

VengefulSLList

Notice that when someone calls removeLast on an SLList, it throws that value away - never to be seen again. But what if those removed values left and started a massive rebellion against us? In this case, we need to remember what those removed (or rather defected >:() values were so we can hunt them down and terminate them later.

We create a new class, VengefulSLList, that remembers all items that have been banished by removeLast.

Like before, we specify in VengefulSLList's class header that it should inherit from SLList.

public class VengefulSLList<Item> extends SLList<Item>

Now, let's give VengefulSLList a method to print out all of the items that have been removed by a call to the removeLast method, printLostItems(). We can do this by adding an instance variable that can keep track of all the deleted items. If we use an SLList to keep track of our items, then we can simply make a call to the print() method to print out all the items.

So far this is what we have:

public class VengefulSLList<Item> extends SLList<Item> {

SLList<Item> deletedItems;

public void printLostItems() {

deletedItems.print();

}

}

VengefulSLList's removeLast should do exactly the same thing that SLList's does, except with one additional operation - adding the removed item to the deletedItems list. In an effort to reuse code, we can override the removeLast method to modify it to fit our needs, and call the removeLast method defined in the parent class, SLList, using the super keyword.

Exercise 4.2.2.

Override the removeLast method to remove the last item, add that item to the deletedItems list, then return it.

Finally, VengefulSLList remembers all items deleted from it, as intended.

public class VengefulSLList<Item> extends SLList<Item> {

SLList<Item> deletedItems;

public VengefulSLList() {

deletedItems = new SLList<Item>();

}

@Override

public Item removeLast() {

Item x = super.removeLast();

deletedItems.addLast(x);

return x;

}

/** Prints deleted items. */

public void printLostItems() {

deletedItems.print();

}

}

Constructors Are Not Inherited

As we mentioned earlier, subclasses inherit all members of the parent class, which includes instance and static variables, methods, and nested classes, but does not include constructors.

While constructors are not inherited, Java requires that all constructors must start with a call to one of its superclass's constructors.

To gain some intuition on why that it is, recall that the extends keywords defines an "is-a" relationship between a subclass and a parent class. If a VengefulSLList "is-an" SLList, then it follows that every VengefulSLList must be set up like an SLList.

Here's a more in-depth explanation. Let's say we have two classes:

public class Human {...}

public class TA extends Human {...}

It is logical for TA to extend Human, because all TA's are Human. Thus, we want TA's to inherit the attributes and behaviors of Humans.

If we run the code below:

TA Christine = new TA();

Then first, a Human must be created. Then, that Human can be given the qualities of a TA. It doesn't make sense for a TA to be constructed without first creating a Human first.

Thus, we can either explicitly make a call to the superclass's constructor, using the super keyword:

public VengefulSLList() {

super();

deletedItems = new SLList<Item>();

}

Or, if we choose not to, Java will automatically make a call to the superclass's no-argument constructor for us.

In this case, adding super() has no difference from the constructor we wrote before. It just makes explicit what was done implicitly by Java before. However, if we were to define another constructor in VengefulSLList, Java's implicit call may not be what we intend to call.

Suppose we had a one-argument constructor that took in an item. If we had relied on an implicit call to the superclass's no-argument constructor, super(), the item passed in as an argument wouldn't be placed anywhere!

So, we must make an explicit call to the correct constructor by passing in the item as a parameter to super.

public VengefulSLList(Item x) {

super(x);

deletedItems = new SLList<Item>();

}

The Object Class

Every class in Java is a descendant of the Object class, or extends the Object class. Even classes that do not have an explicit extends in their class still implicitly extend the Object class.

For example,

- VengefulSLList

extendsSLList explicitly in its class declaration - SLList

extendsObject implicitly

This means that since SLList inherits all members of Object, VengefulSLList inherits all members of SLList and Object, transitively. So, what is to be inherited from Object?

As seen in the documentation for the Object class, the Object class provides operations that every Object should be able to do - like .equals(Object obj), .hashCode(), and toString().

Is-a vs. Has-a

Important Note: The extends keyword defines "is-a", or hypernymic relationships. A common mistake is to instead use it for "has-a", or meronymic relationships.

When extending a class, a wise thing to do would be to ask yourself if the "is-a" relationship makes sense.

Showeris aBathroom? No!VengefulSLListis aSLList? Yes!

Encapsulation

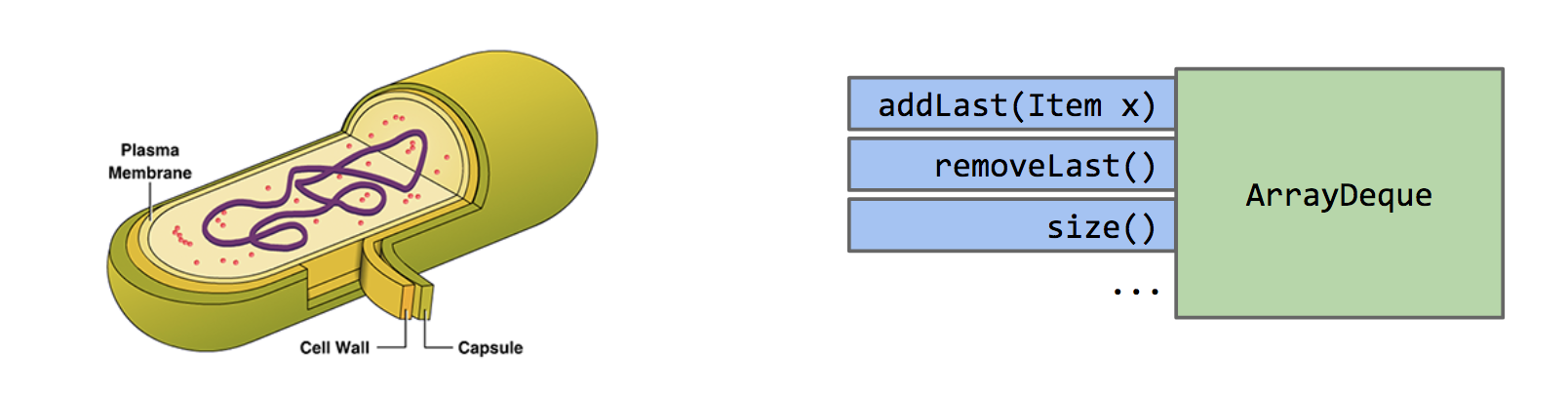

Encapsulation is one of the fundamental principles of object oriented programming, and is one of the approaches that we take as programmers to resist our biggest enemy: complexity. Managing complexity is one of the major challenges we must face when writing large programs.

Some of the tools we can use to fight complexity include hierarchical abstraction (abstraction barriers!) and a concept known as "Design for change". This revolves around the idea that programs should be built into modular, interchangeable pieces that can be swapped around without breaking the system. Additionally, hiding information that others don't need is another fundamental approach when managing a large system.

The root of encapsulation lies in this notion of hiding information from the outside. One way to look at it is to see how encapsulation is analogous to a Human cell. The internals of a cell may be extremely complex, consisting of chromosomes, mitochondria, ribosomes etc., but yet it is fully encapsulated into a single module - abstracting away the complexity inside.

In computer science terms, a module can be defined as a set of methods that work together as a whole to perform a task or set of related tasks. This could be something like a class that represents a list. Now, if the implementation details of a module are kept internally hidden and the only way to interact with it is through a documented interface, then that module is said to be encapsulated.

Take the ArrayDeque class, for example. The outside world is able to utilize and interact with an ArrayDeque through its defined methods, like addLast and removeLast. However, they need not understand the complex details of how the data structure was implemented in order to be able to use it effectively.

Abstraction Barriers

Ideally, a user should not be able to observe the internal workings of, say, a data structure they are using. Fortunately, Java makes it easy to enforce abstraction barriers. Using the private keyword in Java, it becomes virtually impossible to look inside an object - ensuring that the underlying complexity isn't exposed to the outside world.

How Inheritance Breaks Encapsulation

Suppose we had the following two methods in a Dog class. We could have implemented bark and barkMany like so:

public void bark() {

System.out.println("bark");

}

public void barkMany(int N) {

for (int i = 0; i < N; i += 1) {

bark();

}

}

Or, alternatively, we could have implemented it like so:

public void bark() {

barkMany(1);

}

public void barkMany(int N) {

for (int i = 0; i < N; i += 1) {

System.out.println("bark");

}

}

From a user's perspective, the functionality of either of these implementations is exactly the same. However, observe the effect if we were to define a a subclass of Dog called VerboseDog, and override its barkMany method as such:

@Override

public void barkMany(int N) {

System.out.println("As a dog, I say: ");

for (int i = 0; i < N; i += 1) {

bark();

}

}

Exercise 4.2.3.

Given a VerboseDog vd, what would vd.barkMany(3) output, given the first implementation above? The second implementation?

- a: As a dog, I say: bark bark bark

- b: bark bark bark

- c: Something else

As you have seen, using the first implementation, the output is A, while using the second implementation, the program gets caught in an infinite loop. The call to bark() will call barkMany(1), which makes a call to bark(), repeating the process infinitely many times.

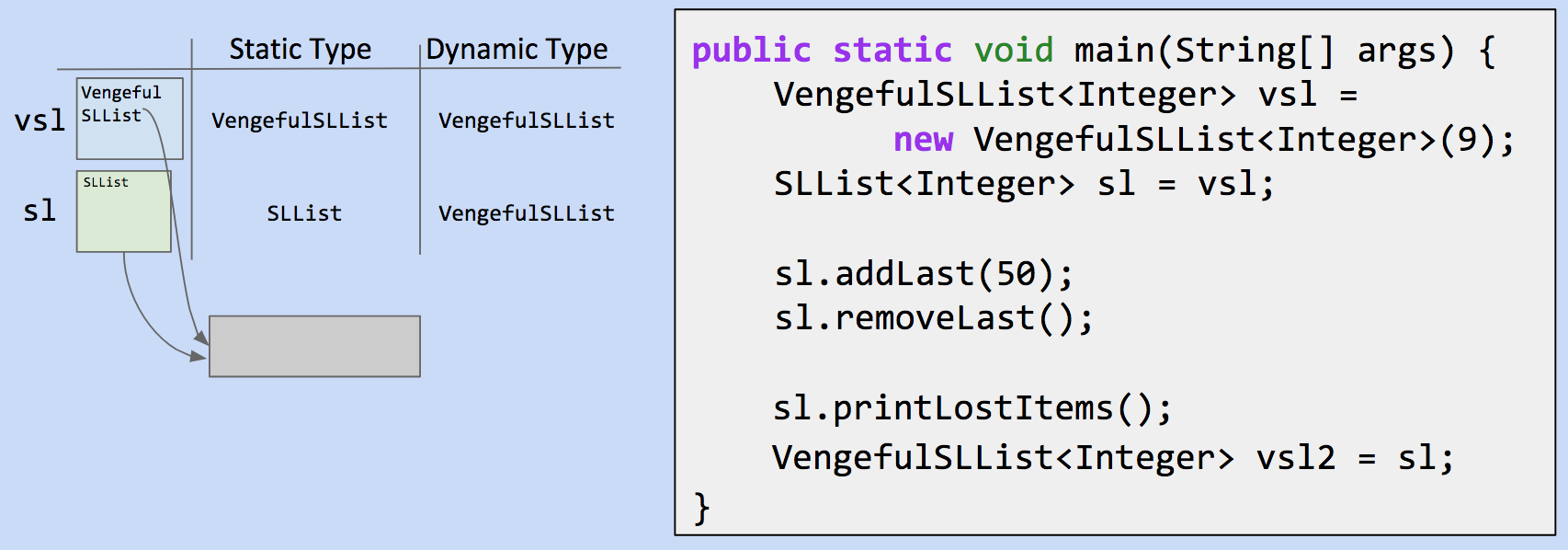

Type Checking and Casting

Before we go into types and casting, let's review dynamic method selection. Recall that dynamic method lookup is the process of determining the method that is executed at runtime based on the dynamic type of the object. Specifically, if a method in SLList is overridden by the VengefulSLList class, then the method that is called at runtime is determined by the run-time type, or dynamic type, of that variable.

Exercise 4.2.4. For each line of code below, decide the following:

- Does that line cause a compilation error?

- Which method uses dynamic selection?

Let's go through this program line by line.

VengefulSLList<Integer> vsl = new VengefulSLList<Integer>(9);

SLList<Integer> sl = vsl;

These two lines above compile just fine. Since VengefulSLList "is-an" SLList, it's valid to put an instance of the VengefulSLList class inside an SLList "container".

sl.addLast(50);

sl.removeLast();

These lines above also compile. The call to addLast is unambiguous, as VengefulSLList did not override or implement it, so the method executed is in SLList.

The removeLast method is overridden by VengefulSLList, however, so we take a look at the dynamic type of sl. Its dynamic type is VengefulSLList, and so dynamic method selection chooses the overridden method in the VengefulSLList class.

sl.printLostItems();

This line above results in a compile-time error. Remember that the compiler determines whether or not something is valid based on the static type of the object. Since sl is of static type SLList, and printLostItems is not defined in the SLList class, the code will not be allowed to run, even though sl's runtime type is VengefulSLList.

VengefulSLList<Integer> vsl2 = sl;

This line above also results in a compile-time error, for a similar reason. In general, the compiler only allows method calls and assignments based on compile-time types. Since the compiler only sees that the static type of sl is SLList, it will not allow a VengefulSLList "container" to hold it.

Expressions

Like variables as seen above, expressions using the new keyword also have compile-time types.

SLList<Integer> sl = new VengefulSLList<Integer>();

Above, the compile-time type of the right-hand side of the expression is VengefulSLList. The compiler checks to make sure that VengefulSLList "is-a" SLList, and allows this assignment,

VengefulSLList<Integer> vsl = new SLList<Integer>();

Above, the compile-time type of the right-hand side of the expression is SLList. The compiler checks if SLList "is-a" VengefulSLList, which it is not in all cases, and thus a compilation error results.

Further, method calls have compile-time types equal to their declared type. Suppose we have this method:

public static Dog maxDog(Dog d1, Dog d2) { ... }

Since the return type of maxDog is Dog, any call to maxDog will have compile-time type Dog.

Poodle frank = new Poodle("Frank", 5);

Poodle frankJr = new Poodle("Frank Jr.", 15);

Dog largerDog = maxDog(frank, frankJr);

Poodle largerPoodle = maxDog(frank, frankJr); //does not compile! RHS has compile-time type Dog

Assigning a Dog object to a Poodle variable, like in the SLList case, results in a compilation error. A Poodle "is-a" Dog, but a more general Dog object may not always be a Poodle, even if it clearly is to you and me (we know that frank and frankJr are both Poodles!). Is there any way around this, when we know for certain that assignment would work?

Casting

Java has a special syntax where you can tell the compiler that a specific expression has a specific compile-time type. This is called "casting". With casting, we can tell the compiler to view an expression as a different compile-time type.

Looking back at the code that failed above, since we know that frank and frankJr are both Poodles, we can cast:

Poodle largerPoodle = (Poodle) maxDog(frank, frankJr); // compiles! Right hand side has compile-time type Poodle after casting

Caution: Casting is a powerful but dangerous tool. Essentially, casting is telling the compiler not to do its type-checking duties - telling it to trust you and act the way you want it to. Here's a possible issue that could arise:

Poodle frank = new Poodle("Frank", 5);

Malamute frankSr = new Malamute("Frank Sr.", 100);

Poodle largerPoodle = (Poodle) maxDog(frank, frankSr); // runtime exception!

In this case, we compare a Poodle and a Malamute. Without casting, the compiler would normally not allow the call to maxDog to compile, as the right hand side compile-time type would be Dog, not Poodle. However, casting allows this code to pass, and when maxDog returns the Malamute at runtime, and we try casting a Malamute as a Poodle, we run into a runtime exception - a ClassCastException.

Higher Order Functions

Taking a little bit of a detour, we are going to introduce higher order functions. A higher order function is a function that treats other functions as data. For example, take this Python program do_twice that takes in another function as input, and applies it to the input x twice.

def tenX(x):

return 10*x

def do_twice(f, x):

return f(f(x))

A call to print(do_twice(tenX, 2)) would apply tenX to 2, and apply tenX again to its result, 20, resulting in 200. How would we do something like this in Java?

In old school Java (Java 7 and earlier), memory boxes (variables) could not contain pointers to functions. What that means is that we could not write a function that has a "Function" type, as there was simply no type for functions.

To get around this we can take advantage of interface inheritance. Let's write an interface that defines any function that takes in an integer and returns an integer - an IntUnaryFunction.

public interface IntUnaryFunction {

int apply(int x);

}

Now we can write a class which implements IntUnaryFunction to represent a concrete function. Let's make a function that takes in an integer and returns 10 times that integer.

public class TenX implements IntUnaryFunction {

/* Returns ten times the argument. */

public int apply(int x) {

return 10 * x;

}

}

At this point, we've written in Java the Python equivalent of the tenX function. Let's write do_twice now.

public static int do_twice(IntUnaryFunction f, int x) {

return f.apply(f.apply(x));

}

A call to print(do_twice(tenX, 2)) in Java would look like this:

System.out.println(do_twice(new TenX(), 2));

Inheritance Cheatsheet

VengefulSLList extends SLList means VengefulSLList "is-an" SLList, and inherits all of SLList's members:

- Variables, methods nested classes

- Not constructors

Subclass constructors must invoke superclass constructor first. The

superkeyword can be used to invoke overridden superclass methods and constructors.

Invocation of overridden methods follows two simple rules:

- Compiler plays it safe and only allows us to do things according to the static type.

- For overridden methods (not overloaded methods), the actual method invoked is based on the dynamic type of the invoking expression

- Can use casting to overrule compiler type checking.