Lists

In Project 0, we use arrays to track the positions of N objects in space. One thing we would not have been able to easily do is change the number of objects after the simulation had begun. This is because arrays have a fixed size in Java that can never change.

An alternate approach would have been to use a list type. You've no doubt used a list data structure at some point in the past. For example, in Python:

L = [3, 5, 6]

L.append(7)

While Java does have a built-in List type, we're going to eschew using it for now. In this chapter, we'll build our own list from scratch, along the way learning some key features of Java.

The Mystery of the Walrus

To begin our journey, we will first ponder the profound Mystery of the Walrus.

Try to predict what happens when we run the code below. Does the change to b affect a? Hint: If you're coming from Python, Java has the same behavior.

Walrus a = new Walrus(1000, 8.3);

Walrus b;

b = a;

b.weight = 5;

System.out.println(a);

System.out.println(b);

Now try to predict what happens when we run the code below. Does the change to x affect y?

int x = 5;

int y;

y = x;

x = 2;

System.out.println("x is: " + x);

System.out.println("y is: " + y);

The answer can be found here.

While subtle, the key ideas that underlie the Mystery of the Walrus will be incredibly important to the efficiency of the data structures that we'll implement in this course, and a deep understanding of this problem will also lead to safer, more reliable code.

Bits

All information in your computer is stored in memory as a sequence of ones and zeros. Some examples:

- 72 is often stored as 01001000

- 205.75 is often stored as 01000011 01001101 11000000 00000000

- The letter H is often stored as 01001000 (same as 72)

- The true value is often stored as 00000001

In this course, we won't spend much time talking about specific binary representations, e.g. why on earth 205.75 is stored as the seemingly random string of 32 bits above. Understanding specific representations is a topic of CS61C, the followup course to 61B.

Though we won't learn the language of binary, it's good to know that this is what is going on under the hood.

One interesting observation is that both 72 and H are stored as 01001000. This raises the question: how does a piece of Java code know how to interpret 01001000?

The answer is through types! For example, consider the code below:

char c = 'H';

int x = c;

System.out.println(c);

System.out.println(x);

If we run this code, we get:

H

72

In this case, both the x and c variables contain the same bits (well, almost...), but the Java interpreter treats them differently when printed.

In Java, there are 8 primitive types: byte, short, int, long, float, double, boolean, and char. Each has different properties that we'll discuss throughout the course, with the exception of short and float, which you'll likely never use.

Declaring a Variable (Simplified)

You can think of your computer as containing a vast number of memory bits for storing information, each of which has a unique address. Many billions of such bits are available to the modern computer.

When you declare a variable of a certain type, Java finds a contiguous block with exactly enough bits to hold a thing of that type. For example, if you declare an int, you get a block of 32 bits. If you declare a byte, you get a block of 8 bits. Each data type in Java holds a different number of bits. The exact number is not terribly important to us in this class.

For the sake of having a convenient metaphor, we'll call one of these blocks a "box" of bits.

In addition to setting aside memory, the Java interpreter also creates an entry in an internal table that maps each variable name to the location of the first bit in the box.

For example, if you declared int x and double y, then Java might decide to use bits 352 through 384 of your computer's memory to store x, and bits 20800 through 20864 to store y. The interpreter will then record that int x starts at bit 352 and y starts at bit 20800. For example, after executing the code:

int x;

double y;

We'd end up with boxes of size 32 and 64 respectively, as shown in the figure below:

The Java language provides no way for you to know the location of the box, e.g. you can't somehow find out that x is in position 352. In other words, the exact memory address is below the level of abstraction accessible to us in Java. This is unlike languages like C where you can ask the language for the exact address of a piece of data. For this reason, I have omitted the addresses from the figure above.

This feature of Java is a tradeoff! Hiding memory locations from the programmer gives you less control, which prevents you from doing certain types of optimizations. However, it also avoids a large class of very tricky programming errors. In the modern era of very low cost computing, this tradeoff is usually well worth it. As the wise Donald Knuth once said: "We should forget about small efficiencies, say about 97% of the time: premature optimization is the root of all evil".

As an analogy, you do not have direct control over your heartbeat. While this restricts your ability to optimize for certain situations, it also avoids the possibility of making stupid errors like accidentally turning it off.

Java does not write anything into the reserved box when a variable is declared. In other words, there are no default values. As a result, the Java compiler prevents you from using a variable until after the box has been filled with bits using the = operator. For this reason, I have avoided showing any bits in the boxes in the figure above.

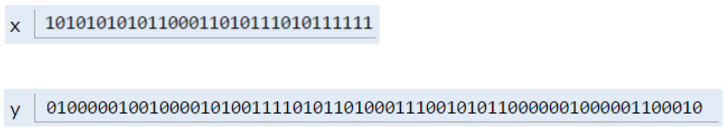

When you assign values to a memory box, it is filled with the bits you specify. For example, if we execute the lines:

x = -1431195969;

y = 567213.112;

Then the memory boxes from above are filled as shown below, in what I call box notation.

The top bits represent -1431195969, and the bottom bits represent 567213.112. Why these specific sequences of bits represent these two numbers is not important, and is a topic covered in CS61C. However, if you're curious, see integer representations and double representations on wikipedia.

Note: Memory allocation is actually somewhat more complicated than described here, and is a topic of CS 61C. However, this model is close enough to reality for our purposes in 61B.

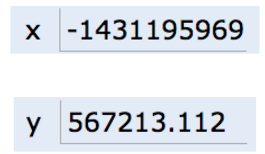

Simplified Box Notation

While the box notation we used in the previous section is great for understanding approximately what's going on under the hood, it's not useful for practical purposes since we don't know how to interpret the binary bits.

Thus, instead of writing memory box contents in binary, we'll write them in human readable symbols. We will do this throughout the rest of the course. For example, after executing:

int x;

double y;

x = -1431195969;

y = 567213.112;

We can represent the program environment using what I call simplified box notation, shown below:

The Golden Rule of Equals (GRoE)

Now armed with simplified box notation, we can finally start to resolve the Mystery of the Walrus.

It turns out our Mystery has a simple solution: When you write y = x, you are telling the Java interpreter to copy the bits from x into y. This Golden Rule of Equals (GRoE) is the root of all truth when it comes to understanding our Walrus Mystery.

int x = 5;

int y;

y = x;

x = 2;

System.out.println("x is: " + x);

System.out.println("y is: " + y);

This simple idea of copying the bits is true for ANY assignment using = in Java. To see this in action, click this link.

Reference Types

Above, we said that there are 8 primitive types: byte, short, int, long, float, double, boolean, char. Everything else, including arrays, is not a primitive type but rather a reference type.

Object Instantiation

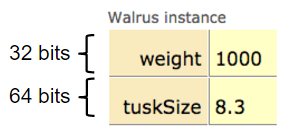

When we instantiate an Object using new (e.g. Dog, Walrus, Planet), Java first allocates a box for each instance variable of the class, and fills them with a default value. The constructor then usually (but not always) fills every box with some other value.

For example, if our Walrus class is:

public static class Walrus {

public int weight;

public double tuskSize;

public Walrus(int w, double ts) {

weight = w;

tuskSize = ts;

}

}

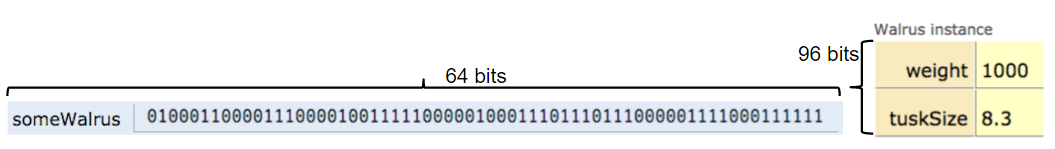

And we create a Walrus using new Walrus(1000, 8.3);, then we end up with a Walrus consisting of two boxes of 32 and 64 bits respectively:

In real implementations of the Java programming language, there is actually some additional overhead for any object, so a Walrus takes somewhat more than 96 bits. However, for our purposes, we will ignore such overhead, since we will never interact with it directly.

The Walrus we've created is anonymous, in the sense that it has been created, but it is not stored in any variable. Let's now turn to variables that store objects.

Reference Variable Declaration

When we declare a variable of any reference type (Walrus, Dog, Planet, array, etc.), Java allocates a box of 64 bits, no matter what type of object.

At first glance, this might seem to lead to a Walrus Paradox. Our Walrus from the previous section required more than 64 bits to store. Furthermore, it may seem bizarre that no matter the type of object, we only get 64 bits to store it.

However, this problem is easily resolved with the following piece of information: the 64 bit box contains not the data about the walrus, but instead the address of the Walrus in memory.

As an example, suppose we call:

Walrus someWalrus;

someWalrus = new Walrus(1000, 8.3);

The first line creates a box of 64 bits. The second line creates a new Walrus, and the address is returned by the new operator. These bits are then copied into the someWalrus box according to the GRoE.

If we imagine our Walrus weight is stored starting at bit 5051956592385990207 of memory, and tuskSize starts at bit 5051956592385990239, we might store 5051956592385990207 in the Walrus variable. In binary, 5051956592385990207 is represented by the 64 bits 0100011000011100001001111100000100011101110111000001111000111111, giving us in box notation:

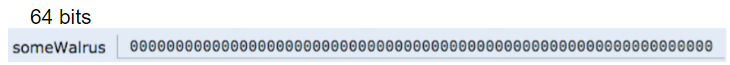

We can also assign the special value null to a reference variable, corresponding to all zeros.

Box and Pointer Notation

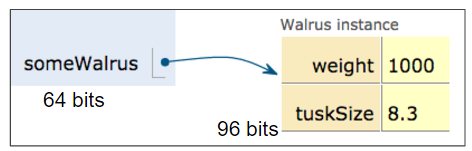

Just as before, it's hard to interpret a bunch of bits inside a reference variable, so we'll create a simplified box notation for reference variable as follows:

- If an address is all zeros, we will represent it with null.

- A non-zero address will be represented by an arrow pointing at an object instantiation.

This is also sometimes called "box and pointer" notation.

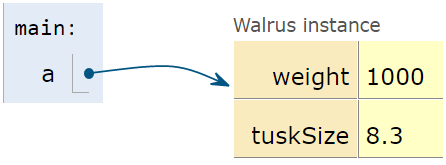

For the examples from the previous section, we'd have:

Resolving the Mystery of the Walrus

We're now finally ready to resolve, fully and completely, the Mystery of the Walrus.

Walrus a = new Walrus(1000, 8.3);

Walrus b;

b = a;

After the first line is executed, we have:

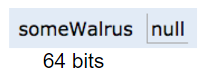

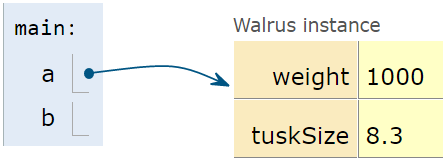

After the second line is executed, we have:

Note that above, b is undefined, not null.

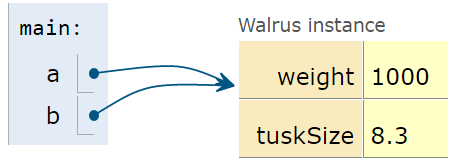

According to the GRoE, the final line simply copies the bits in the a box into the b box. Or in terms of our visual metaphor, this means that b will copy exactly the arrow in a and now show an arrow pointing at the same object.

And that's it. There's no more complexity than this.

Parameter Passing

When you pass parameters to a function, you are also simply copying the bits. In other words, the GRoE also applies to parameter passing. Copying the bits is usually called "pass by value". In Java, we always pass by value.

For example, consider the function below:

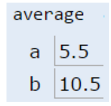

public static double average(double a, double b) {

return (a + b) / 2;

}

Suppose we invoke this function as shown below:

public static void main(String[] args) {

double x = 5.5;

double y = 10.5;

double avg = average(x, y);

}

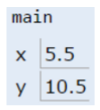

After executing the first two lines of this function, the main method will have two boxes labeled x and y containing the values shown below:

When the function is invoked, the average function has its own scope with two new boxes labeled as a and b, and the bits are simply copied in. This copying of bits is what we refer to when we say "pass by value".

If the average function were to change a, then x in main would be unchanged, since the GRoE tells us that we'd simply be filling in the box labeled a with new bits.

Test Your Understanding

Exercise 2.1.1: Suppose we have the code below:

public class PassByValueFigure {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Walrus walrus = new Walrus(3500, 10.5);

int x = 9;

doStuff(walrus, x);

System.out.println(walrus);

System.out.println(x);

}

public static void doStuff(Walrus W, int x) {

W.weight = W.weight - 100;

x = x - 5;

}

}

Does the call to doStuff have an effect on walrus and/or x? Hint: We only need to know the GRoE to solve this problem.

Instantiation of Arrays

As mentioned above, variables that store arrays are reference variables just like any other. As an example, consider the declarations below:

int[] x;

Planet[] planets;

Both of these declarations create memory boxes of 64 bits. x can only hold the address of an int array, and planets can only hold the address of a Planet array.

Instantiating an array is very similar to instantiating an object. For example, if we create an integer array of size 5 as shown below:

x = new int[]{0, 1, 2, 95, 4};

Then the new keyword creates 5 boxes of 32 bits each and returns the address of the overall object for assignment to x.

Objects can be lost if you lose the bits corresponding to the address. For example if the only copy of the address of a particular Walrus is stored in x, then x = null will cause you to permanently lose this Walrus. This isn't necessarily a bad thing, since you'll often decide you're done with an object, and thus it's safe to simply throw away the reference. We'll see this when we build lists later in this chapter.

The Law of the Broken Futon

You might ask yourself why we spent so much time and space covering what seems like a triviality. This is probably especially true if you have prior Java experience. The reason is that it is very easy for a student to have a half-cocked understanding of this issue, allowing them to write code, but without true comprehension of what's going on.

While this might be fine in the short term, in the long term, doing problems without full understanding may doom you to failure later down the line. There's a blog post about this so-called Law of the Broken Futon that you might find interesting.

IntLists

Now that we've truly understood the Mystery of the Walrus, we're ready to build our own list class.

It turns out that a very basic list is trivial to implement, as shown below:

public class IntList {

public int first;

public IntList rest;

public IntList(int f, IntList r) {

first = f;

rest = r;

}

}

You may remember something like this from 61a called a "Linked List".

Such a list is ugly to use. For example, if we want to make a list of the numbers 5, 10, and 15, we can either do:

IntList L = new IntList(5, null);

L.rest = new IntList(10, null);

L.rest.rest = new IntList(15, null);

Alternately, we could build our list backwards, yielding slightly nicer but harder to understand code:

IntList L = new IntList(15, null);

L = new IntList(10, L);

L = new IntList(5, L);

While you could in principle use the IntList to store any list of integers, the resulting code would be rather ugly and prone to errors. We'll adopt the usual object oriented programming strategy of adding helper methods to our class to perform basic tasks.

size and iterativeSize

We'd like to add a method size to the IntList class so that if you call L.size(), you get back the number of items in L.

Consider writing a size and iterativeSize method before reading the rest of this chapter. size should use recursion, and iterativeSize should not. You'll probably learn more by trying on your own before seeing how I do it. The two videos provide a live demonstration of how one might implement these methods.

My size method is as shown below:

/** Return the size of the list using... recursion! */

public int size() {

if (rest == null) {

return 1;

}

return 1 + this.rest.size();

}

The key thing to remember about recursive code is that you need a base case. In this situation, the most reasonable base case is that rest is null, which results in a size 1 list.

Exercise: You might wonder why we don't do something like if (this == null) return 0;. Why wouldn't this work?

Answer: Think about what happens when you call size. You are calling it on an object, for example L.size(). If L were null, then you would get a NullPointer error!

My iterativeSize method is as shown below. I recommend that when you write iterative data structure code that you use the name p to remind yourself that the variable is holding a pointer. You need that pointer because you can't reassign "this" in Java. The followups in this Stack Overflow Post offer a brief explanation as to why.

/** Return the size of the list using no recursion! */

public int iterativeSize() {

IntList p = this;

int totalSize = 0;

while (p != null) {

totalSize += 1;

p = p.rest;

}

return totalSize;

}

get

While the size method lets us get the size of a list, we have no easy way of getting the ith element of the list.

Exercise: Write a method get(int i) that returns the ith item of the list. For example, if L is 5 -> 10 -> 15, then L.get(0) should return 5, L.get(1) should return 10, and L.get(2) should return 15. It doesn't matter how your code behaves for invalid i, either too big or too small.

For a solution, see the lecture video above or the lectureCode repository.

Note that the method we've written takes linear time! That is, if you have a list that is 1,000,000 items long, then getting the last item is going to take much longer than it would if we had a small list. We'll see an alternate way to implement a list that will avoid this problem in a future lecture.