Throwing Exceptions (legacy)

When something goes really wrong in a program, we want to break the normal flow of control. It may not make sense to continue on, or it may not be possible at all. In these cases, the program throws an exception.

Let’s look at what might be a familiar case: an IndexOutOfBounds exception.

The code below inserts the value 5 into an ArrayMap under the key “hello”, then tries to print out the value when getting “yolp.”

public static void main (String[] args) {

ArrayMap<String, Integer> am = new ArrayMap<String, Integer>();

am.put("hello", 5);

System.out.println(am.get("yolp"));

}

What happens when we run this? The program attempts to access a key which doesn’t exist, and crashes! This results in the following error message:

$ java ExceptionDemo

Exception in thread "main" java.lang.ArrayIndexOutOfBoundsException: -1

at ArrayMap.get(ArrayMap.java:38)

at ExceptionDemo.main(ExceptionDemo.java:6)

This is an implicit exception, an error thrown by Java itself. We can learn a little bit from this message: we see that the program crashed because of an ArrayIndexOutOfBoundsException; but it doesn’t tell us very much besides that. You may have encountered similarly unhelpful error messages during your own programming endeavors. So how can we be more helpful to the user of our program?

We can throw our own exceptions, using the throw keyword. This lets us provide our own error messages which may be more informative to the user. We can also provide information to error-handling code within our program. This is an explicit exception because we purposefully threw it as the programmer.

In the case above, we might implement get with a check for a missing key, that throws a more informative exception:

public V get(K key) {

intlocation = findKey(key);

if(location < 0) {

throw newIllegalArgumentException("Key " + key + " does not exist in map."\);

}

return values[findKey(key)];

}

Now, instead of java.lang.ArrayIndexOutOfBoundsException: -1, we see:

$java ExceptionDemo

Exception in thread "main" java.lang.IllegalArgumentException: Key yolp does not exist in map.

at ArrayMap.get(ArrayMap.java:40)

at ExceptionDemo.main(ExceptionDemo.java:6)

Catching Exceptions

As we've seen, sometimes things go wrong while the program is running. Java handles these "exceptional events" by throwing an exception. In this section, we'll see what else we can do when such an exception is thrown.

Consider these error situations:

- You try to use 383,124 gigabytes of memory.

- You try to cast an Object as a Dog, but dynamic type is not Dog.

- You try to call a method using a reference variable that is equal to null.

- You try to access index -1 of an array.

So far, we've seen Java crash and print error messages with implicit exceptions:

Object o = "mulchor";

Planet x = (Planet) o;

resulting in:

Exception in thread "main" java.lang.ClassCastException:

java.lang.String cannot be cast to Planet

And above, we saw how to provide more informative errors by using explicit exceptions:

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println("ayyy lmao");

throw new RuntimeException("For no reason.");

}

which produces the error:

$ java Alien

ayyy lmao

Exception in thread "main" java.lang.RuntimeException: For no reason.

at Alien.main(Alien.java:4)

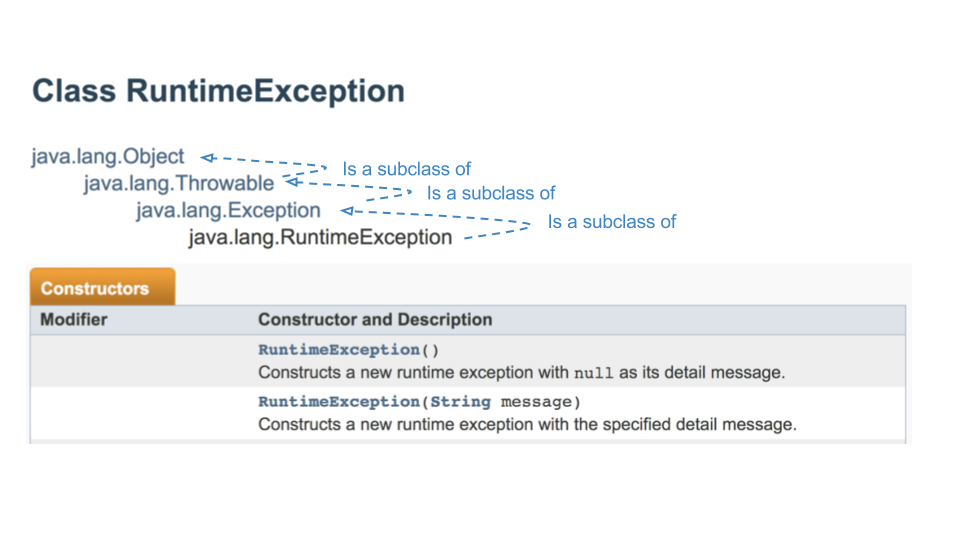

In this example, note a familiar construction: new RuntimeException("For no reason."). This looks a lot like instantiating a class -- because that's exactly what it is. A RuntimeException is just a Java Object, like any other.

So far, thrown exceptions cause code to crash. But we can ‘catch’ exceptions instead, preventing the program from crashing. The keywords try and catch break the normal flow of the program, protecting it from exceptions.

Consider the following example:

Dog d = new Dog("Lucy", "Retriever", 80);

d.becomeAngry();

try {

d.receivePat();

} catch (Exception e) {

System.out.println("Tried to pat: " + e);

}

System.out.println(d);

The output of this code might be:

$ java ExceptionDemo

Tried to pat: java.lang.RuntimeException: grrr... snarl snarl

Lucy is a displeased Retriever weighing 80.0 standard lb units.

Here we see that when we try and pat the dog when the dog is angry, it throws a RuntimeException, with the helpful error message "grrr...snarl snarl." But, it does continue on, and print out the state of the dog in the final line! This is because we caught the exception.

This might not seem particularly useful yet. But we can also use a catch statement to take corrective action.

Dog d = new Dog("Lucy", "Retriever", 80);

d.becomeAngry();

try {

d.receivePat();

} catch (Exception e) {

System.out.println(

"Tried to pat: " + e);

d.eatTreat("banana");

}

d.receivePat();

System.out.println(d);

In this version of our code, we soothe the dog with a treat. Now when we try and pat it again, the method executes without failing.

$ java ExceptionDemo

Tried to pat: java.lang.RuntimeException: grrr... snarl snarl

Lucy munches the banana

Lucy enjoys the pat.

Lucy is a happy Retriever weighing 80.0 standard lb units.

In the real world, this corrective action might be extending an antenna on a robot when an exception is thrown by an operation expecting a ready antenna. Or perhaps we simply want to write the error to a log file for later analysis.

The Philosophy Of Exceptions

Exceptions aren't the only way to do error handling. But they do have some advantages. Most importantly, they keep error handling conceptually separate from the rest of the program.

Let's consider some psuedocode for a program that reads from a file:

func readFile: {

open the file;

determine its size;

allocate that much memory;

read the file into memory;

close the file;

}

A lot of things might go wrong here: maybe the file doesn't exist, maybe there isn't enough memory, or the reading fails.

Without exceptions, we might handle the errors like this:

func readFile: {

open the file;

if (theFileIsOpen) {

determine its size;

if (gotTheFileLength) {

allocate that much memory;

} else {

return error("fileLengthError");

}

if (gotEnoughMemory) {

read the file into memory;

if (readFailed) {

return error("readError");

}

...

} else {

return error("memoryError");

}

} else {

return error("fileOpenError")

}

}

But this super messy! And deeply frustrating to read.

With exceptions, we might rewrite this as:

func readFile: {

try {

open the file;

determine its size;

allocate that much memory;

read the file into memory;

close the file;

} catch (fileOpenFailed) {

doSomething;

} catch (sizeDeterminationFailed) {

doSomething;

} catch (memoryAllocationFailed) {

doSomething;

} catch (readFailed) {

doSomething;

} catch (fileCloseFailed) {

doSomething;

}

}

Here, we first do all the things associated with reading our file, and wrap them in a try statement. Then, if an error happens anywhere in that sequence of operations, it will get caught by the appropriate catch statement. We can provide distinct behaviors for each type of exception.

The key benefit of the exceptions version, in contrast to the naive version above, is that the code flows in a clean narrative. First, try to do the desired operations. Then, catch any errors. Good code feels like a story; it has a certain beauty to its construction. That clarity makes it easier to both write and maintain over time.

Uncaught Exceptions

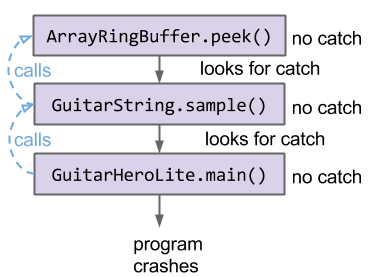

When an exception is thrown, it descends the call stack.

If the peek() method does not explicitly catch the exception, the exception will propagate to the calling function, sample(). We can think of this as popping the current method off the stack, and moving to the next method below it. If sample() also fails to catch the exception, it moves to main().

If the exception reaches the bottom of the stack without being caught, the program crashes and Java provides a message for the user, printing out the stack trace. Ideally the user is a programmer with the power to do something about it.

java.lang.RuntimeException in thread “main”:

at ArrayRingBuffer.peek:63

at GuitarString.sample:48

at GuitarHeroLite.java:110

We can see by looking at the stack trace where the error occurred: on line 63 of ArrayRingBuffer.peek(), after being called by line 48 of GuitarString.sample(), after being called by the main method of GuitarHeroLite.java on line 110. But this isn't super helpful unless the user also happens to be a programmer with the power to do something about the error.