The Problem

Recall the two list classes we created last week: SLList and AList. If you take a look at their documentation, you'll notice that they are very similar. In fact, all of their supporting methods are the same!

Suppose we want to write a class WordUtilsthat includes functions we can run on lists of words, including a method that calculates the longest string in an SLList.

Exercise 4.1.1. Try writing this method by yourself. The method should take in an SLList of strings and return the longest string in the list.

Here is the method that we came up with.

public static String longest(SLList<String> list) {

int maxDex = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < list.size(); i += 1) {

String longestString = list.get(maxDex);

String thisString = list.get(i);

if (thisString.length() > longestString.length()) {

maxDex = i;

}

}

return list.get(maxDex);

}

How do we make this method work for AList as well?

All we really have to do is change the method's signature: the parameter

SLList<String> list

should be changed to

AList<String> list

Now we have two methods in our WordUtils class with exactly the same method name.

public static String longest(SLList<String> list)

and

public static String longest(AList<String> list)

This is actually allowed in Java! It's something called method overloading. When you call WordUtils.longest, Java knows which one to run according to what kind of parameter you supply it. If you supply it with an AList, it will call the AList method. Same with an SLList.

It's nice that Java is smart enough to know how to deal with two of the same methods for different types, but overloading has several downsides:

- It's super repetitive and ugly, because you now have two virtually identical blocks of code.

- It's more code to maintain, meaning if you want to make a small change to the

longestmethod such as correcting a bug, you need to change it in the method for each type of list. - If we want to make more list types, we would have to copy the method for every new list class.

Hypernyms, Hyponyms, and Interface Inheritance

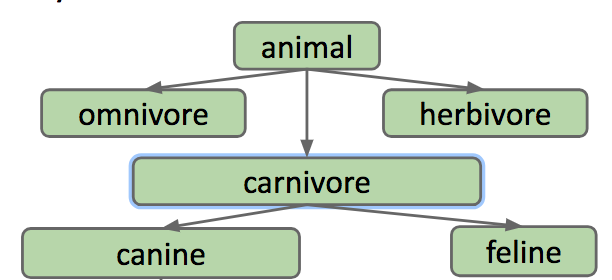

In the English language and life in general, there exist logical hierarchies to words and objects.

Dog is what is called a hypernym of poodle, malamute, husky, etc. In the reverse direction, poodle, malamute, and husky, are hyponyms of dog.

These words form a hierarchy of "is-a" relationships:

- a poodle "is-a" dog

- a dog "is-a" canine

- a canine "is-a" carnivore

- a carnivore "is-an" animal

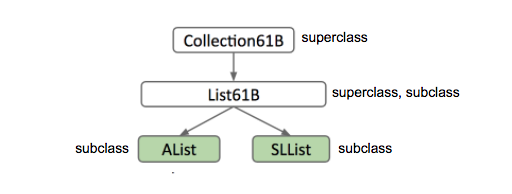

The same hierarchy goes for SLLists and ALists! SLList and AList are both hyponyms of a more general list.

We will formalize this relationship in Java: if a SLList is a hyponym of List61B, then the SLList class is a subclass of the List61B class and the List61B class is a superclass of the SLList class.

Figure 4.1.1

In Java, in order to express this hierarchy, we need to do two things:

- Step 1: Define a type for the general list hypernym -- we will choose the name List61B.

- Step 2: Specify that SLList and AList are hyponyms of that type.

The new List61B is what Java calls an interface. It is essentially a contract that specifies what a list must be able to do, but it doesn't provide any implementation for those behaviors. Can you think of why?

Here is our List61B interface. At this point, we have satisfied the first step in establishing the relationship hierarchy: creating a hypernym.

public interface List61B<Item> {

public void addFirst(Item x);

public void add Last(Item y);

public Item getFirst();

public Item getLast();

public Item removeLast();

public Item get(int i);

public void insert(Item x, int position);

public int size();

}

Now, to complete step 2, we need to specify that AList and SLList are hyponyms of the List61B class. In Java, we define this relationship in the class definition.

We will add to

public class AList<Item> {...}

a relationship-defining word: implements.

public class AList<Item> implements List61B<Item>{...}

implements List61B<Item> is essentially a promise. AList is saying "I promise I will have and define all the attributes and behaviors specified in the List61B interface"

Now we can edit our longest method in WordUtils to take in a List61B

Overriding

We promised we would implement the methods specified in List61B in the AList and SLList classes, so let's go ahead and do that.

When implementing the required functions in the subclass, it's useful (and actually required in 61B) to include the @Override tag right on top of the method signature. Here, we have done that for just one method.

@Override

public void addFirst(Item x) {

insert(x, 0);

}

It is good to note that even if you don’t include this tag, you are still overriding the method. So technically, you don't have to include it. However, including the tag acts as a safeguard for you as the programmer by alerting the compiler that you intend to override this method. Why would this be helpful you ask? Well, it's kind of like having a proofreader! The compiler will tell you if something goes wrong in the process.

Say you want to override the addLast method. What if you make a typo and accidentally write addLsat? If you don't include the @Override tag, then you might not catch the mistake, which could make debugging a more difficult and painful process. Whereas if you include @Override, the compiler will stop and prompt you to fix your mistakes before your program even runs.

Interface Inheritance

Interface Inheritance refers to a relationship in which a subclass inherits all the methods/behaviors of the superclass. As in the List61B class we defined in the Hyponyms and Hypernyms section, the interface includes all the method signatures, but not implementations. It's up to the subclass to actually provide those implementations.

This inheritance is also multi-generational. This means if we have a long lineage of superclass/subclass relationships like in Figure 4.1.1, AList not only inherits the methods from List61B but also every other class above it all the way to the highest superclass AKA AList inherits from Collection.

GRoE

Recall the Golden Rule of Equals we introduced in the first chapter. This means whenever we make an assignment

a = b

, we copy the bits from b into a, with the requirement that b is the same type as a. You can't assign Dog b = 1

or Dog b = new Cat()

because 1 is not a Dog and neither is Cat.

Let's try to apply this rule to the longest method we wrote previously in this chapter.

public static String longest(List61B<String> list) takes in a List61B. We said that this could take in AList and SLList as well, but how is that possible since AList and List61B are different classes? Well, recall that AList shares an "is-a" relationship with List61B, Which means an AList should be able to fit into a List61B box!

Exercise 4.1.2 Do you think the code below will compile? If so, what happens when it runs?

public static void main(String[] args) {

List61B<String> someList = new SLList<String>();

someList.addFirst("elk");

}

Here are possible answers:

- Will not compile.

- Will compile, but will cause an error on the new line

- When it runs, an SLList is created and its address is stored in the someList variable, but it crashes on someList.addFirst() since the List class doesn't implement addFirst;

- When it runs, and SLList is created and its address is stored in the someList variable. Then the string "elk" is inserted into the SLList referred to by addFirst.

Implementation Inheritance

Previously, we had an interface List61B that only had method headers identifying what List61B's should do. But, now we will see that we can write methods in List61B that already have their implementation filled out. These methods identify how hypernyms of List61B should behave.

In order to do this, you must include the default keyword in the method signature.

If we define this method in List61B

default public void print() {

for (int i = 0; i < size(); i += 1) {

System.out.print(get(i) + " ");

}

System.out.println();

}

Then everything that implements the List61B class can use the method!

However, there is one small inefficiency in this method. Can you catch it?

For an SLList, the get method needs to jump through the entirety of the list. during each call. It's much better to just print while jumping through!

We want SLList to print a different way than the way specified in its interface. To do this, we need to override it. In SLList, we implement this method;

@Override

public void print() {

for (Node p = sentinel.next; p != null; p = p.next) {

System.out.print(p.item + " ");

}

}

Now, whenever we call print() on an SLList, it will call this method instead of the one in List61B.

You may be wondering, how does Java know which print() to call? Good question. Java is able to do this due to something called dynamic method selection.

We know that variables in java have a type.

List61B<String> lst = new SLList<String>();

In the above declaration and instantiation, lst is of type "List61B". This is called the "static type"

However, the objects themselves have types as well. the object that lst points to is of type SLList. Although this object is intrinsically an SLList (since it was declared as such), it is also a List61B, because of the “is-a” relationship we explored earlier. But, because the object itself was instantiated using the SLList constructor, We call this its "dynamic type".

Aside: the name “dynamic type” is actually quite semantic in its origin! Should lst be reassigned to point to an object of another type, say a AList object, lst’s dynamic type would now be AList and not SLList! It’s dynamic because it changes based on the type of the object it’s currently referring to.

When Java runs a method that is overriden, it searches for the appropriate method signature in it's dynamic type and runs it.

IMPORTANT: This does not work for overloaded methods!

Say there are two methods in the same class

public static void peek(List61B<String> list) {

System.out.println(list.getLast());

}

public static void peek(SLList<String> list) {

System.out.println(list.getFirst());

}

and you run this code

SLList<String> SP = new SLList<String>();

List61B<String> LP = SP;

SP.addLast("elk");

SP.addLast("are");

SP.addLast("cool");

peek(SP);

peek(LP);

The first call to peek() will use the second peek method that takes in an SLList. The second call to peek() will use the first peek method which takes in a List61B. This is because the only distinction between two overloaded methods is the types of the parameters. When Java checks to see which method to call, it checks the static type and calls the method with the parameter of the same type.

Interface Inheritance vs Implementation Inheritance

How do we differentiate between "interface inheritance" and "implementation inheritance"? Well, you can use this simple distinction:

- Interface inheritance (what): Simply tells what the subclasses should be able to do.

- EX) all lists should be able to print themselves, how they do it is up to them.

- Implementation inheritance (how): Tells the subclasses how they should behave.

- EX) Lists should print themselves exactly this way: by getting each element in order and then printing them.

When you are creating these hierarchies, remember that the relationship between a subclass and a superclass should be an "is-a" relationship. AKA Cat should only implement Animal Cat is an Animal. You should not be defining them using a "has-a" relationship. Cat has-a Claw, but Cat definitely should not be implementing Claw.

Finally, Implementation inheritance may sound nice and all but there are some drawbacks:

- We are fallible humans, and we can't keep track of everything, so it's possible that you overrode a method but forgot you did.

- It may be hard to resolve conflicts in case two interfaces give conflicting default methods.

It encourages overly complex code

What's Next?

- Discussion 4 Inheritance