In this section, we'll build a new class called AList that can be used to store arbitrarily long lists of data, similar to our DLList. Unlike the DLList, the AList will use arrays to store data instead of a linked list.

Linked List Performance Puzzle

Suppose we wanted to write a new method for DLList called int get(int i). Why would get be slow for long lists compared to getLast? For what inputs would it be especially slow?

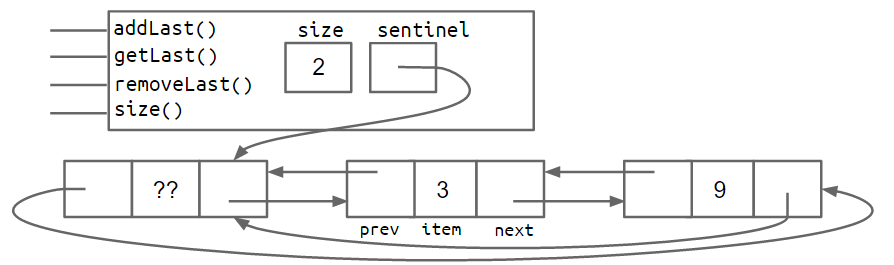

You may find the figure below useful for thinking about your answer.

Linked List Performance Puzzle Solution

It turns out that no matter how clever you are, the get method will usually be slower than getBack if we're using the doubly linked list structure described in section 2.3.

This is because, since we only have references to the first and last items of the list, we'll always need to walk through the list from the front or back to get to the item that we're trying to retrieve. For example, if we want to get item #417 in a list of length 10,000, we'll have to walk across 417 forward links to get to the item we want.

In the very worst case, the item is in the very middle and we'll need to walk through a number of items proportional to the length of the list (specifically, the number of items divided by two). In other words, our worst case execution time for get is linear in the size of the entire list. This in contrast to the runtime for getBack, which is constant, no matter the size of the list. Later in the course, we'll formally define runtimes in terms of big O and big Theta notation. For now, we'll stick to an informal understanding.

Our First Attempt: The Naive Array Based List

Accessing the ith element of an array takes constant time on a modern computer. This suggests that an array-based list would be capable of much better performance for get than a linked-list based solution, since it can simply use bracket notation to get the item of interest.

If you'd like to know why arrays have constant time access, check out this Quora post.

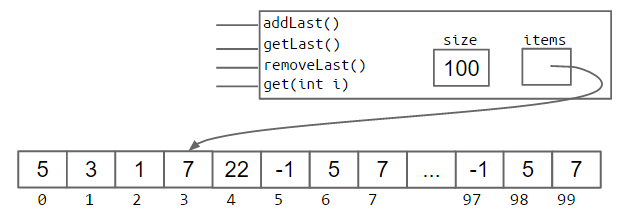

Optional Exercise 2.5.1: Try to build an AList class that supports addLast, getLast, get, and size operations. Your AList should work for any size array up to 100. For starter code, see https://github.com/Berkeley-CS61B/lectureCode/tree/master/lists4/DIY.

My solution has the following handy invariants.

- The position of the next item to be inserted (using

addLast) is alwayssize. - The number of items in the AList is always

size. - The position of the last item in the list is always

size - 1.

Other solutions might be slightly different.

removeLast

The last operation we need to support is removeLast. Before we start, we make the following key observation: Any change to our list must be reflected in a change in one or more memory boxes in our implementation.

This might seem obvious, but there is some profundity to it. The list is an abstract idea, and the size, items, and items[i] memory boxes are the concrete representation of that idea. Any change the user tries to make to the list using the abstractions we provide (addLast, removeLast) must be reflected in some changes to these memory boxes in a way that matches the user's expectations. Our invariants provide us with a guide for what those changes should look like.

Optional Exercise 2.5.2: Try to write removeLast. Before starting, decide which of size, items, and items[i] needs to change so that our invariants are preserved after the operation, i.e. so that future calls to our methods provide the user of the list class with the behavior they expect.

Naive Resizing Arrays

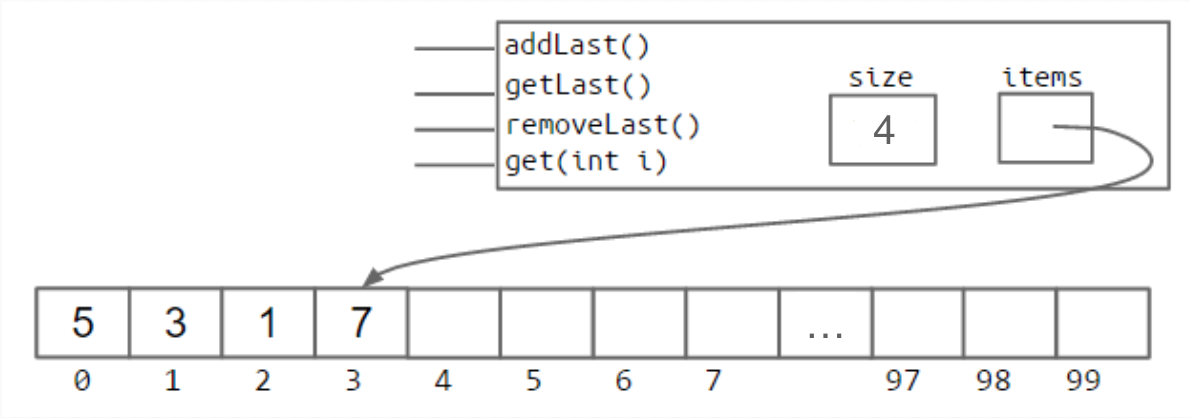

Optional Exercise 2.5.3: Suppose we have an AList in the state shown in the figure below. What will happen if we call addLast(11)? What should we do about this problem?

The answer, in Java, is that we simply build a new array that is big enough to accomodate the new data. For example, we can imagine adding the new item as follows:

int[] a = new int[size + 1];

System.arraycopy(items, 0, a, 0, size);

a[size] = 11;

items = a;

size = size + 1;

The process of creating a new array and copying items over is often referred to as "resizing". It's a bit of a misnomer since the array doesn't actually change size, we are just making a new one that has a bigger size.

Exercise 2.5.4: Try to implement the addLast(int i) method to work with resizing arrays.

Analyzing the Naive Resizing Array

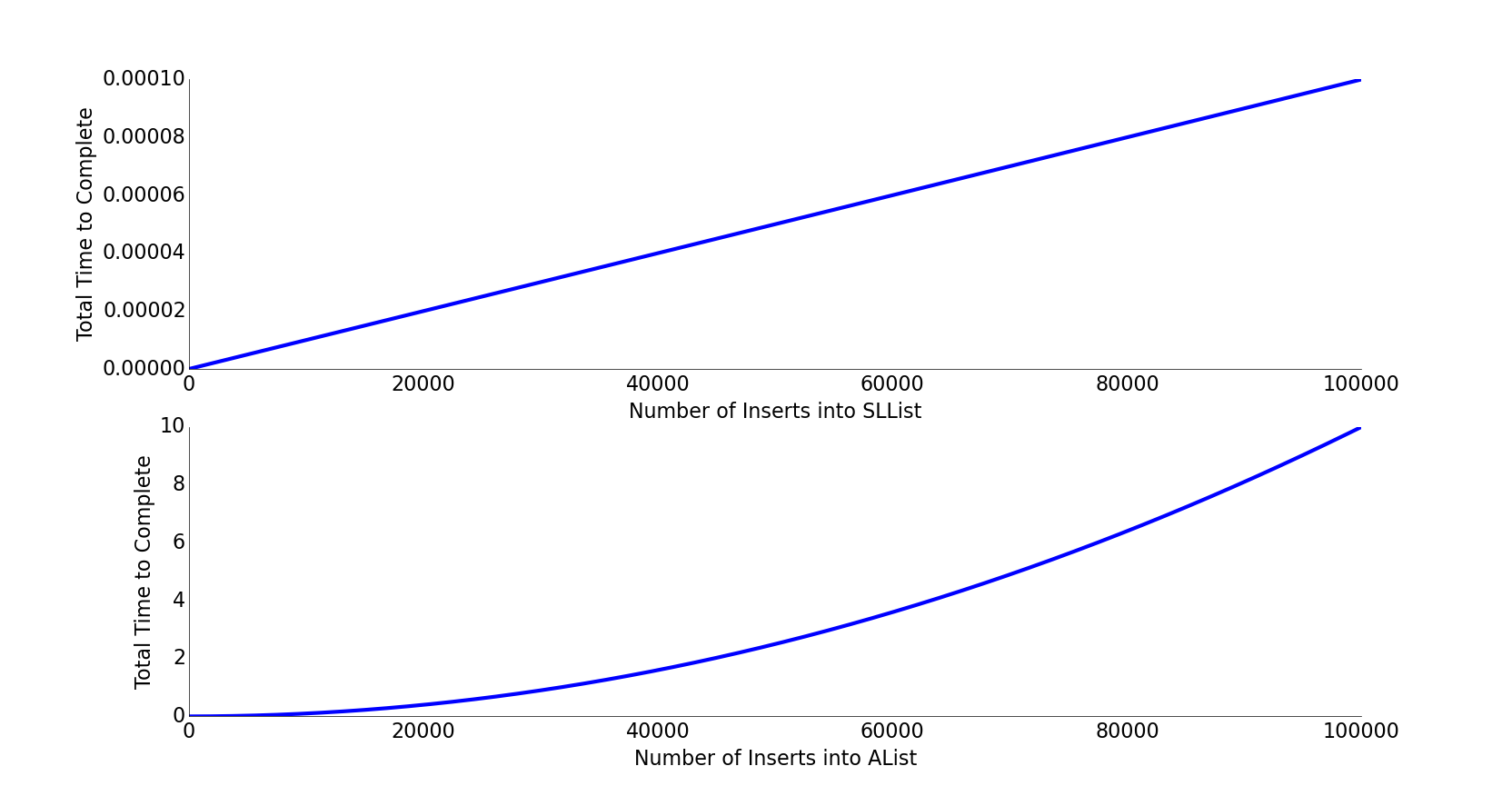

The approach that we attempted in the previous section has terrible performance. By running a simple computational experiment where we call addLast 100,000 times, we see that the SLList completes so fast that we can't even time it. By contrast our array based list takes several seconds.

To understand why, consider the following exercise:

Exercise 2.5.5: Suppose we have an array of size 100. If we call insertBack two times, how many total boxes will we need to create and fill throughout this entire process? How many total boxes will we have at any one time, assuming that garbage collection happens as soon as the last reference to an array is lost?

Exercise 2.5.6: Starting from an array of size 100, approximately how many memory boxes get created and filled if we call addLast 1,000 times?

Creating all those memory boxes and recopying their contents takes time. In the graph below, we plot total time vs. number of operations for an SLList on the top, and for a naive array based list on the bottom. The SLList shows a straight line, which means for each add operation, the list takes the same additional amount of time. This means each single operation takes constant time! You can also think of it this way: the graph is linear, indicating that each operation takes constant time, since the integral of a constant is a line.

By contrast, the naive array list shows a parabola, indicating that each operation takes linear time, since the integral of a line is a parabola. This has significant real world implications. For inserting 100,000 items, we can roughly compute how much longer by computing the ratio of N^2/N. Inserting 100,000 items into our array based list takes (100,000^2)/100,000 or 100,000 times as long. This is obviously unacceptable.

Geometric Resizing

We can fix our performance problems by growing the size of our array by a multiplicative amount, rather than an additive amount. That is, rather than adding a number of memory boxes equal to some resizing factor RFACTOR:

public void insertBack(int x) {

if (size == items.length) {

resize(size + RFACTOR);

}

items[size] = x;

size += 1;

}

We instead resize by multiplying the number of boxes by RFACTOR.

public void insertBack(int x) {

if (size == items.length) {

resize(size * RFACTOR);

}

items[size] = x;

size += 1;

}

Repeating our computational experiment from before, we see that our new AList completes 100,000 inserts in so little time that we don't even notice. We'll defer a full analysis of why this happens until the final chapter of this book.

Memory Performance

Our AList is almost done, but we have one major issue. Suppose we insert 1,000,000,000 items, then later remove 990,000,000 items. In this case, we'll be using only 10,000,000 of our memory boxes, leaving 99% completely unused.

To fix this issue, we can also downsize our array when it starts looking empty. Specifically, we define a "usage ratio" R which is equal to the size of the list divided by the length of the items array. For example, in the figure below, the usage ratio is 0.04.

In a typical implementation, we halve the size of the array when R falls to less than 0.25.

Generic ALists

Just as we did before, we can modify our AList so that it can hold any data type, not just integers. To do this, we again use the special angle braces notation in our class and substitute our arbitrary type parameter for integer wherever appropriate. For example, below, we use Glorp as our type parameter.

There is one significant syntactical difference: Java does not allow us to create an array of generic objects due to an obscure issue with the way generics are implemented. That is, we cannot do something like:

Glorp[] items = new Glorp[8];

Instead, we have to use the awkward syntax shown below:

Glorp[] items = (Glorp []) new Object[8];

This will yield a compilation warning, but it's just something we'll have to live with. We'll discuss this in more details in a later chapter.

The other change we make is that we null out any items that we "delete". Whereas before, we had no reason to zero out elements that were deleted, with generic objects, we do want to null out references to the objects that we're storing. This is to avoid "loitering". Recall that Java only destroys objects when the last reference has been lost. If we fail to null out the reference, then Java will not garbage collect the objects that have been added to the list.

This is a subtle performance bug that you're unlikely to observe unless you're looking for it, but in certain cases could result in a significant wastage of memory.