Industrial Strength Syntax

In the previous parts of this book, we've talked about various data structures and the way that Java supports their implementation. In this chapter, we'll discuss a variety of supplementary topics that are used in industrial strength implementations of Java programs.

This is not meant to be a comprehensive guide to Java, but rather a highlight of features that are likely to be useful to you while working on this course.

Automatic Conversions

Autoboxing and Unboxing

As we saw in the previous chapter, we can define classes which have generic type variables using the <> syntax, e.g. LinkedListDeque<Item> and ArrayDeque<Item>. When we want to instantiate an object whose class uses generics, we have to substitute the generic with a concrete class, i.e. specify what type of items are going to go into that class.

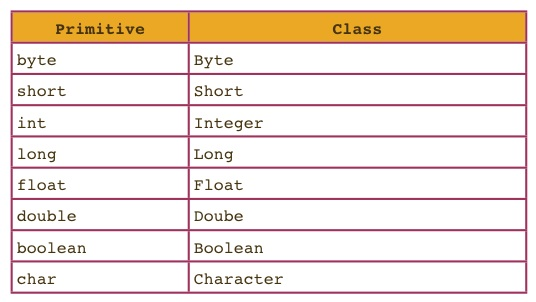

Recall that Java has 8 primitive types -- all other types are reference types. One particular feature of Java is that we cannot provide a primitive type as an actual type argument for generics, e.g. ArrayDeque<int> is a syntax error. Instead, we use ArrayDeque<Integer>. For each primitive type, we use the corresponding reference type as shown in the table below. These reference types are called "wrapper classes".

Naively, we'd assume that this would result in having to manually convert between primitive and reference types when using a generic data structure. For example, we might imagine having to do the following:

public class BasicArrayList {

public static void main(String[] args) {

ArrayList<Integer> L = new ArrayList<Integer>();

L.add(new Integer(5));

L.add(new Integer(6));

/* Use the Integer.valueOf method to convert to int */

int first = L.get(0).valueOf();

}

}

Writing code like above can be a bit annoying. Luckily, Java can implicitly convert between primitive and wrapper types, so the code below works just fine:

public class BasicArrayList {

public static void main(String[] args) {

ArrayList<Integer> L = new ArrayList<Integer>();

L.add(5);

L.add(6);

int first = L.get(0);

}

}

The reason this works is that Java will automatically "box" and "unbox" values between a primitive type and its corresponding reference type. That is, if Java expects a wrapper type, like Integer, and you provide a primitive type, like int, it will "autobox" the integer. For example, if we have the function:

public static void blah(Integer x) {

System.out.println(x);

}

And we call it using:

int x = 20;

blah(x);

Then Java implicitly creates a new Integer with value 20, resulting in a call to equivalent to calling blah(new Integer(20)). This process is known as autoboxing.

Likewise, if Java expected a primitive:

public static void blahPrimitive(int x) {

System.out.println(x);

}

but you give it a value of the corresponding wrapper type:

Integer x = new Integer(20);

blahPrimitive(x);

It will automatically unbox the integer, equivalent to calling the Integer class's valueOf method.

Caveats

There are a few things to keep in mind when it comes to autoboxing and unboxing:

Arrays are never autoboxes or auto-unboxed, e.g. if you have an array of integers

int[] x, and try to put its address into a variable of typeInteger[], the compiler will not allow your program to compile.Autoboxing and unboxing also has a measurable performance impact. That is, code that relies on autoboxing and unboxing will be slower than code that eschews such automatic conversions.

Additionally, wrapper types use much more memory than primitive types. On most modern comptuers, not only must your code hold a 64 bit reference to the object, but every object also requires 64 bits of overhead used to store things like the dynamic type of the object.

Widening

Similar to the autoboxing/unboxing process, Java will also automatically widen a primitive if needed. Specifically, if a program expects a primitive of type T2 and is given a variable of type T1, and type T2 can take on a wider range of values than T1, the the variable will be implicitly cast to type T2.

For example, doubles in Java are wider than ints. If we have the function shown below:

public static void blahDouble(double x) {

System.out.println(“double: “ + x);

}

We can call it with an int argument:

int x = 20;

blahDouble(x);

The effect is the same as if we'd done blahDouble((double) x). Thanks Java!

If you want to go from a wider type to a narrower type, you must manually cast. For example, if you have the method below:

public static void blahInt(int x) {

System.out.println(“int: “ + x);

}

Then we'd need to use a cast if we want to call this method using a double value, e.g.

double x = 20;

blahInt((int) x);

For more details on widening, including a full description of what types are wider than others, see the official Java documentation.