Efficient Programming

“An engineer will do for a dime what any fool will do for a dollar” -- Paul Hilfinger

Efficiency comes in two flavors:

1.) Programming cost.

- How long does it take to develop your programs?

- How easy is it to read, modify, and maintain your code?

2.) Execution cost (starting next week).

- How much time does your program take to execute?

- How much memory does your program require?

Today, we will be focusing on how to reduce programming cost. Of course, want to keep programming costs low, both so we can write code faster and so we can have less frustrated people which will also help us write code faster (people don't code very fast when they are frustrated).

Some helpful Java features discussed in 61B:

- Packages.

- Good: Organizing, making things package private

- Bad: Specific

- Static type checking.

- Good: Checks for errors early , reads more like a story

- Bad: Not too flexible, (casting)

- Inheritance.

- Good: Reuse of code

- Bad: “Is a”, the path of debugging gets annoying, can’t instantiate, implement every method of an interface

We will explore some new ways in this chapter!

Encapsulation

We will first define a few terms:

- Module: A set of methods that work together as a whole to perform some task or set of related tasks.

- Encapsulated: A module is said to be encapsulated if its implementation is completely hidden, and it can be accessed only through a documented interface.

API's

An API(Application Programming Interface) of an ADT is the list of constructors and methods and a short description of each.

API consists of syntactic and semantic specification.

- Compiler verifies that syntax is met.

- AKA, everything specified in the API is present.

- Tests help verify that semantics are correct.

- AKA everything actually works the way it should.

- Semantic specification usually written out in English (possibly including usage examples). Mathematically precise formal specifications are somewhat possible but not widespread.

ADT's

ADT's (Abstract Data Structures) are high-level types that are defined by their behaviors, not their implementations.

i.e.) Deque in Proj1 was an ADT that had certain behaviors (addFirst, addLast, etc.). But, the data structures we actually used to implement it was ArrayDeque and LinkedListDeque

Some ADT's are actually special cases of other ADT's. For example, Stacks and Queues are just lists that have even more specific behavior.

Exercise 8.1.1

Write a Stack class using a Linked List as its underlying data structure. You only need to implement a single function: push(Item x). Make sure to make the class generic with "Item" being the generic type!

You may have written it a few different ways. Let's look at three popular solutions:

public class ExtensionStack<Item> extends LinkedList<Item> {

public void push(Item x) {

add(x);

}

}

This solution uses extension. it simply borrow the methods from LinkedList<Item> and uses them as its own.

public class DelegationStack<Item> {

private LinkedList<Item> L = new LinkedList<Item>();

public void push(Item x) {

L.add(x);

}

}

This approach uses Delegation. It creates a Linked List object and calls its methods to accomplish its goal.

public class StackAdapter<Item> {

private List L;

public StackAdapter(List<Item> worker) {

L = worker;

}

public void push(Item x) {

L.add(x);

}

}

This approach is similar to the previous one, except it can use any class that implements the List interface (Linked List, ArrayList, etc).

Warning: be mindful of the difference between "is-a" and "has-a" relationships.

- A cat has-a claw

- A cat is-a feline

Earlier in the section define that delegation is accomplished by passing in a class while extension is defined as inheriting (just because it may be hard to notice at first glance).

Delegation vs Extension: Right now it may seem that Delegation and Extension are pretty much interchangeable; however, there are some important differences that must be remembered when using them.

Extension tends to be used when you know what is going on in the parent class. In other words, you know how the methods are implemented. Additionally, with extension, you are basically saying that the class you are extending from acts similarly to the one that is doing the extending. On the other hand, Delegation is when you do not want to consider your current class to be a version of the class that you are pulling the method from.

Views: Views are an alternative representation of an existed object. Views essentially limit the access that the user has to the underlying object. However, changes done through the views will affect the actual object.

/** Create an ArrayList. */

List<String> L = new ArrayList<>();

/** Add some items. */

L.add(“at”); L.add(“ax”); …

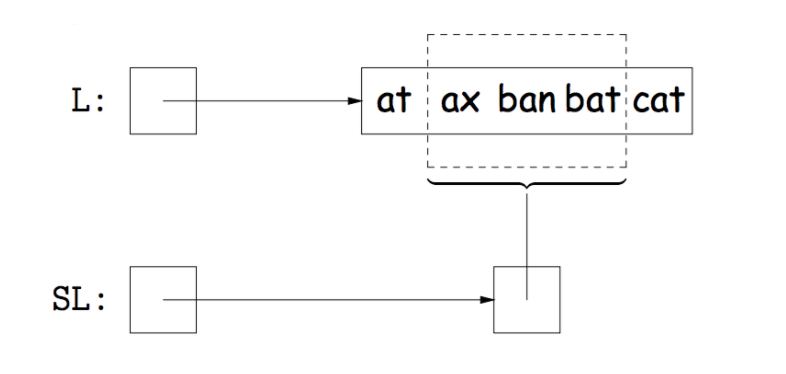

Say you only want a list from index 1 and 4. Then you can use a method called sublist do this by the following and you will

/** subList me up fam. */

List<String> SL = l.subList(1, 4);

/** Mutate that thing. */

SL.set(0, “jug”);

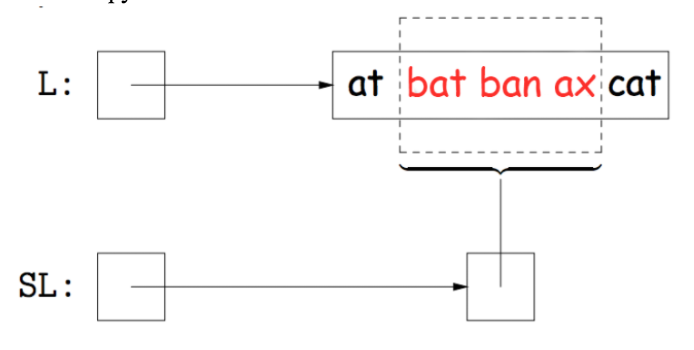

Now why is this useful? Well say we want to reverse only part of the list. For example in the below image, we would want to reverse ax ban bat in the above picture.

The most intuitive way is to create a method that takes in a list object and the indices which should be reversed. However, this can be a bit painful because we add some extraneous logic.

To get around doing this, we can just create a general reverse function that takes in a list and reverses that list. Because views mutates the underlying object that it represents, we can create a sublist like earlier and reverse the sublist. The end result would actually mutate the actual list and not the copy.

This is all fine and dandy. However, it lends itself to an issue. You are claiming that you can give a list object that when manipulated, can affect the original list object- that’s a bit weird. Just thinking “How do you return an actual List but still have it affect another List?” is a bit confusing. Well the answer is access methods.

The first thing to notice is that the sublist method returns a list type. Additionally, there is a defined class called Sublist which extends AbstractList. Since Abstract List it implements the List interface it and Sublist are List types.

List<Item> sublist(int start, int end){

Return new this.Sublist(start,end);

}

This first thing to notice from the above code is that subList returns a List type.

Private class Sublist extends AbstractList<Item>{

Private int start end;

Sublist(inst start, int end){...}

}

Now the reason the sublist function returns a List is because the class SubList extends AbstractList. Since AbstractList implements the List interface both it and Sublist are List Types.

public Item get(int k){return AbstractList.this.get(start+k);}

public void add(int l, Item x){AbstractList.this.add(start+k, x); end+=1}

An observation that should be made is that getting the kth item from our sublist is the same as getting the the kth item from our original list with an offset equal to our start index. Because we are using a get method of our outer class (the most parent one) we change our original list.

Similarly, adding an element to our sublist is the same as adding an element to our original list with an offset equal to the start index of the sublist.

The Takeaway:

- APIs are pretty hard to design; however, having a coherent design philosophy can make your code much cleaner and easier to deal with.

- Inheritance is tempting to use frequently, but it has problems and should be use sparingly, only when you are certain about attributes of your classes (both those being extended and doing the extending).